'Welcome to being an artist – this is the deal' Inside the Lonely Writers Club

Writing is a lonely endeavor but Metalabel’s Austin Robey is trying to bring community to the process

The act of writing can seem romantic. It’s easy to imagine Walt Whitman squirreled away, writing from derelict cabins in the woods. The absinthe-sipping Hemingway in a dimly lit Parisian cabaret. A heartbroken Bon Iver writing his breakthrough album For Emma, Forever Ago also in a cabin. The teenage Mary Shelley, scribbling on vellum beneath the candlelight. And the Beats and Bob Dylan and punk laureates and Kurt Cobain, banging away at their typewriters. These archetypes evoke tales and scenes on the edges of life, legendary and barely real. But writing, in the real act of it, is also lonely.

A couple weeks ago, I stumbled upon a tweet from Metalabel’s Austin Robey.

I’d missed Robey proposing a newsletter label in June, and the subsequent invitation to join him in the Lonely Writers Club, and even the essay he penned on the club’s impetus and intentions.

“For me, writing became a way to build a public thesis and connect with like-minded people from around the world,” he wrote. “This year, however, I’ve been struggling. I haven’t published any personal writing in months. I feel stuck.”

When his invitation was greeted with great interest, Robey conceived a remedy, rallying around an “emotional truth,” he wrote: “I’m not alone.”

What emerged was the Lonely Writers Club, “a new ephemeral peer group for writers providing creative mutual support. A space where interested people can transform their writing practices, collaborate with others, and create writing labels with people who share similar interests and visions.”

A lonely writer myself, I joined 199 other people in signing up, filling out a roster that included both hobbyists and New York Times-published scribes – a reminder that loneliness doesn’t necessarily subside with experience.

The club met for 90 minutes each Wednesday for three weeks. Yancey Strickler, co-founder of Metalabel and erstwhile Kickstarter co-captain, commenced the first meeting, setting the tone with a vulnerable reflection on his own relationship with writing.

About five years ago, after a decade spent working as a journalist, Strickler gave himself a year to write his book, This Could Be Our Future. “It was amazing,” he said, speaking of the time and space he had to create, “but of course it was also very lonely.” Seeking wisdom, Strickler reached out to a painter friend who told him, “Welcome to being an artist – this is the deal.”

The most grueling – and resonant – bit, though, was how Strickler felt when the creative act had finished and he had to navigate the moil of promotional labor: publishing, marketing and otherwise attracting attention. “I had a zombie ego, where I was constantly looking for attention and feedback,” he said. “Even when something good would happen, it was immediately erased. There was no being satisfied – I was constantly looking for affirmation.”

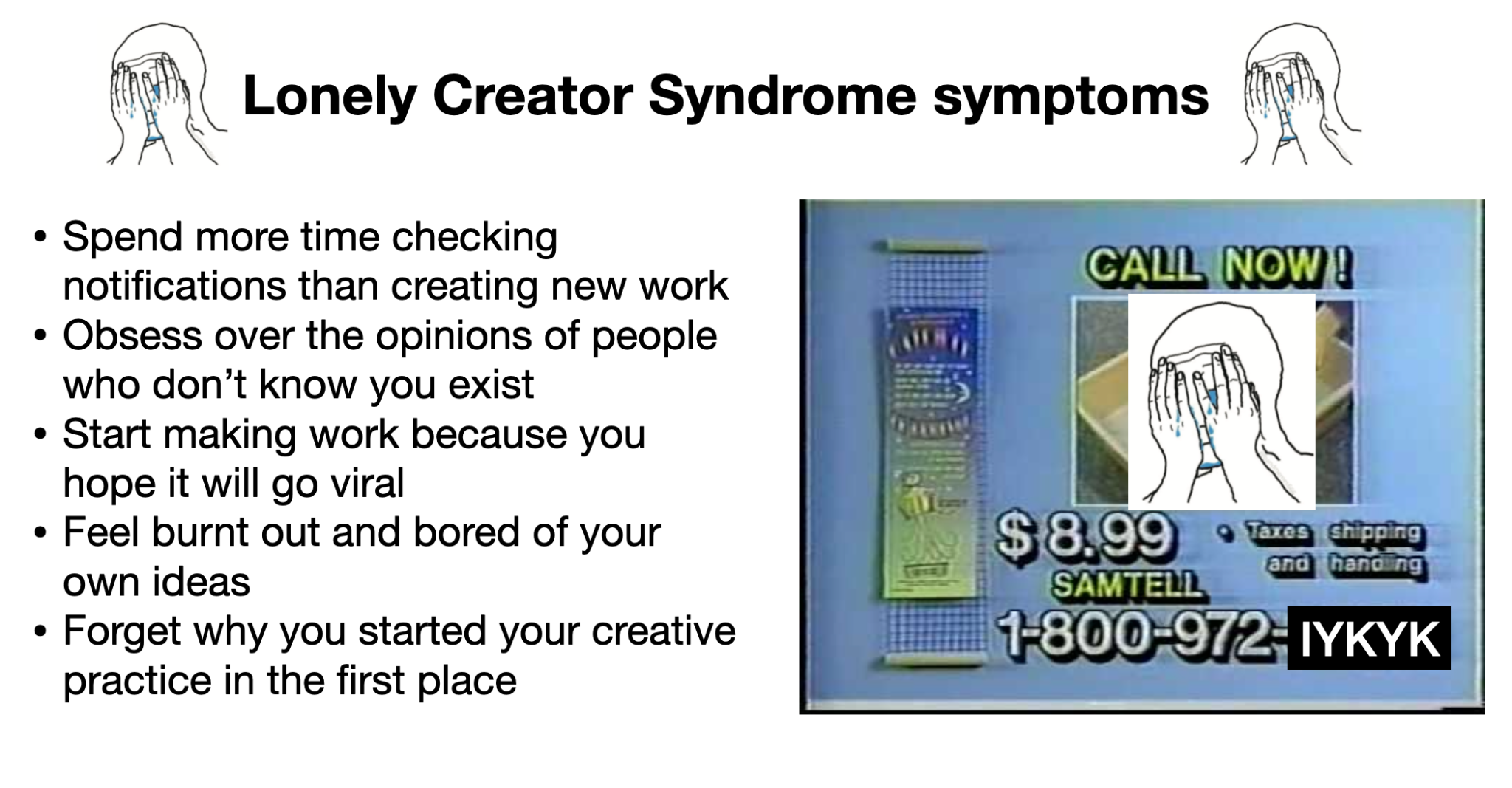

”Now I think of this as lonely creator syndrome,” he continued, “this notion of spending more time looking for feedback and attention, spending more time on that than you do actually making your own work…Even when good things happened they would bring me no joy.”

Strickler hit a low point, and from that nadir, Metalabel emerged.

Lonely Writers Club is Metalabel’s ninth release and latest experiment in challenging the notion that creative things are to be done alone. If the creator economy is creativity in single-player mode, “a metalabel is creativity in multiplayer mode,” and “a model for collaboration, collective world-building, and mutual support.”

In the past two years, Metalabel has run Assembly – a community accelerator for emerging metalabels – orchestrated ten Quality Drops – collaborative on-chain releases that raised more than a million dollars for 146 creators and 20 labels – and built Chorus, an open-source collective publishing tool that posts a tweet only after a certain threshold of people say it be so.

I’ve written about Metalabel’s projects regularly since it emerged, largely because of the feeling to which “zombie ego” gave a name – that reckoning with the din of modern-day media and the sheepish but very real desire to be seen. It makes more sense to do it together.

Read more: Nvak Collective’s Sammy Del Real on Using Web3 to Better Distribute Opportunity in the Music Industry

But the game is rigged. In 2017 I interviewed Ben Frost, the composer best known for scoring the labyrinthine German thriller Dark. At the time he’d made some headlines for a cherry-picked interview quote in which he essentially said there’s too much music and that some people should stop making it.

When I mentioned that moment to Frost, he chalked it up to a moment of frustration about the sheer amount of noise in the world. We’re embattled creators, beset with misaligned platform incentives and algorithms that reward broad appeal, encouraging the interminable pursuit of more instead of better. Suddenly, all our fellow creators are competitors instead of collaborators. It’s becoming harder and harder to find people, and to truly be found.

With “lonely creator syndrome” fresh in our minds, we wrote our own statements of intent and then we shared them with one another. Perusing them – and the active Zoom chat – was like peering into the crevasse of my mind. There were all the pains of promotional labor, and ideas like “the worst part isn’t writing, it’s hitting send” – those bubbling terrors one tries to ignore but can’t.

But then there was the immediate relief that comes from realizing you’re not alone in feeling them. And alongside those terrors were a great many dreams and resonant ideas for easing such pains – like providing comfort to each other as we all leave our comfort zones, normalizing irregular cadences to reduce the pressure of hitting send, building collectively run writers labels and writing bands, and imagining conversation as a technology that facilitates writing.

It was a heartening first foray that expanded post-gathering into various thematic Discord channels – like music, web3, journalism, accountability and shared writing resources – and a shared members directory.

The two sessions that followed – titled “going deeper” and “going forward,” respectively – featured zine-creating guest speakers who are actively subverting the institution of lonely process by publishing together.

Brian Eno back in the day

It all felt very “scenius” – a term Brian Eno devised as a companion to “genius.” Where genius is the creative intelligence of an individual, scenius is the creative intelligence of a community. It’s an awareness that each genius we individualize and celebrate is, in actuality, a representative of an entire flourishing scene.

In Eno fashion, we did joint writing exercises that pushed us to communicate the goals of our writing, and the scenes and new ideas that might emerge from it. In a music-focused breakout room after one such exercise, ten of us spent time imagining what our world would be like if we could quantify culture. What if “return on investment,” a classic measure of success on Wall Street, was calculated in cultural returns? Or if success metrics were defined not by technocrats but by the artists themselves?

This is living proof that conversation facilitates writing – and by extension, the richness that connection can bring to the creative process. Perhaps some eager and optimistic technologist will see this piece and revolutionize the ways in which we measure value (please do!).

In the final session, Strickler guided us in a task that began by sitting in silence for five minutes, sans screens, observing something in our respective physical spaces. Afterwards we jotted down the experience and shared them.

Each entry was a poetic glimpse into another’s world, and it framed an existential exercise for considering how our writing might function within our own. There were simple questions like, “what do you want as a writer? What will having that do for you? And what stands in the way of you doing it?” But seeking the answers was far less simple.

In intimate three-person groups we tried to communicate our visions, and explored how they can begin or evolve in practical ways – leaning away from the alluring sheen of the romantic archetypes we may have in our minds.

And that was a theme of Lonely Writers Club, to eschew the romance of single-player mode while confronting the realities of writing. It was a catalyst for both revitalizing personal writing practices and, hopefully, the creation of new zines and writing labels and accountability partnerships.

Robey even used ChatGPT to generate writing “crushes” and label ideas from people with aligned intentions – fodder for scenius adventures, and a playful end to what was a generative reprieve from my lonely writing. Lonely Writers Club was a chance to connect and commiserate, and to work toward more mindful – and collaborative – approaches to creation and attention gathering.

Before I wrote this, I sat silently for five minutes in the same spot I did during our exercise. I stared out my window, across the cobblestone street of our little square. There’s a tall maple in the garden, and I could hear that lovely whooshing that only comes from wind passing through leaves. It had probably been there all day, skipping my notice. There’s an entire world around us, filled with people and trees and other great things. Writing doesn’t have to be lonely. And as I tuned myself to the wind, I could almost hear Whitman’s whisper in the whoosh: "We were together. I forget the rest."