Russell Sheffield and the Arc of History, From The Beatles and Trident Studios to Creating Songbits and NFT-based Fractional Song Ownership

Russell Sheffield’s journey has taken him from London’s Trident Studios and the Beatles to creating Songbits which allows for NFT-based fractional song ownership

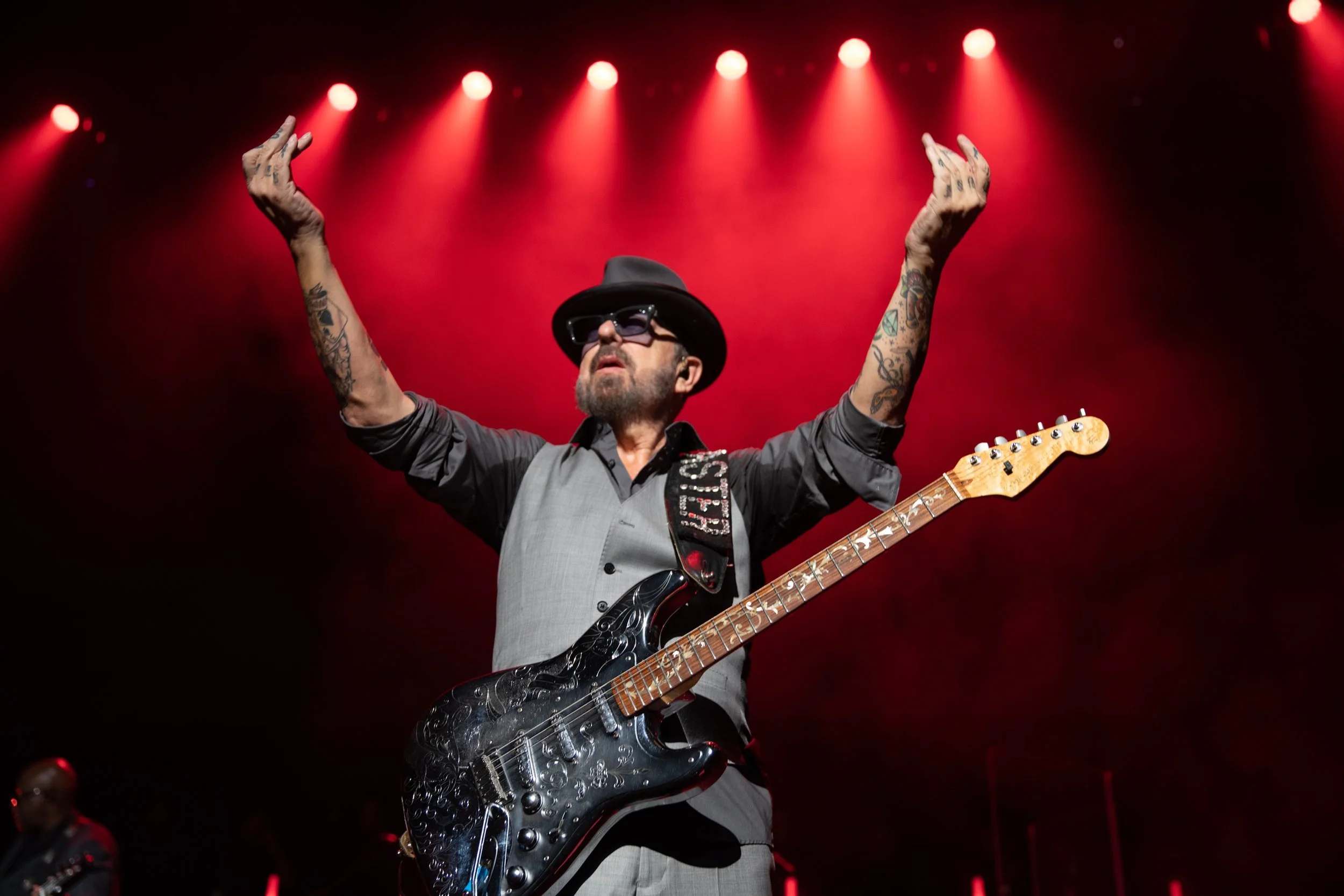

above: Russell Sheffield

On my way to meet Russell Sheffield, the co-founder of Songbits, I listened to “Hey Jude” – one of the Beatles tracks recorded at Trident Studios, a renowned studio created and run by his father, Norman.

The song is a paragon of Paul McCartney’s inimitable songwriting talents, as intimate as it is anthemic. McCartney purportedly composed the track to comfort John Lennon’s son, Julian, during his parents’ separation. Tempering the succor of the first half is the electrifying coda known the whole world round: McCartney’s impassioned shrieks (“Cary Grant on heat,” as he described it) over the accompanying 36-piece orchestra. As Norman Sheffield remembers it, McCartney had to rouse the orchestra members from their torpor – a product of their patronizing attitude toward The Beatles dilettante musicianship – by jumping atop a grand piano to conduct with gusto.

The younger Sheffield is fully aware of that iconic history – and his father’s place in it – as he’s embarked on Songbits, his non-fungible-token (NFT) marketplace that’s backed by Grammy award winning producer and Eurythmics co-lead, Dave Stewart. The new platform integrates directly with Trackd, a private social network for musicians and collaborative eight-track recording studio app that Sheffield launched in 2016. Songbits is leveraging web3 technology to further bolster the connection forged between artist and fan.

Democratizing music

I met Sheffield, who’s stocky with an affable temperament, at the Sanderson – a posh hotel just five minutes walk from the building that housed Trident Studios. We sat at a small table in the back, downing lattes and discussing Songbits.

“I was really looking at how to democratize music, and the one thing that's been missing in the last 10 years [with] the rise of streaming is the relationship between artists and fans,” Russell told me. “[The inspiration] is a reference back to dad, when he signed Queen in ‘72.”

When labels balked at Queen, his father famously became their first manager, helping them garner their first major contract with EMI Records. (Even after an eventual rift over mistreatment followed by a defamation lawsuit, Queen still contracted Trillion Studios – a film studio Norman helped build – to record the video for “Bohemian Rhapsody,” often regarded as the first modern music video.)

“Everything he put around the band was focused on the band and building incredible engagement,” Sheffield shared. “The audience and the shows were amazing.”

From the imagery to the eight-track setup to the musicians-first mindset, Trackd and Songbits are explicitly rooted in the ethos and history of Trident Studios. And through his newest platform – currently in private alpha and expected to launch within weeks – Sheffield is still invoking the Trident spirit.

Considering its brief 13-year history from 1968 to 1981, Trident’s discography is nonpareil: Lou Reed’s Transformer. T. Rex’s Electric Warrior. Carly Simon’s No Secrets. Joan Armatradings’s Whatever's for Us. The Rolling Stones, Frank Zappa, and Tina Turner all recorded at Trident. Elton John recorded seven records there. David Bowie, four – including Hunky Dory, Space Oddity, and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, which upon Bowie’s death, inspired a plaque to be hung outside the erstwhile studio space.

“The Bowie thing came around as one celebration of an artist, but I think it deserves a much bigger recognition in the whole culture of the music industry,” Sheffield told me. “I don't think there’s ever been a studio that's produced as many number ones in such a short period…There should be a plaque for the music – full stop – that happened in this building.”

Passersby unaware of the David Bowie plaque (blue circle) hanging above the old Trident Studios building

Nestled in an unassuming alleyway in Soho, 17 St. Anne's Court now sits between a tanning salon and a wellness spa. A barber, bubble tea shop, locksmith, and a couple cafes round out the lane. The Bowie plaque hangs about 15 feet in the air, high enough so that everyone passes by without knowing what they've missed.

Trident was founded when Russell was four, born out of his father’s frustrations with contemporary recording spaces. The elder Sheffield was a drummer for the British band The Hunters and for Cliff Richard (the third-top-selling artist in UK Singles Chart history behind The Beatles and Elvis Presley). He was vexed by the stale recording environments he saw while working in places like Abbey Road.

“You literally had engineers in white lab coats who would set your kit up for you,” Russell told me. “He had the idea for a studio built for musicians by musicians, so he went off and raised some money in the city – a startup before a startup, I suppose. And that was Trident Studios.”

Within a month of opening, Trident had its first number one: Manfred Mann’s “My Name is Jack.” More success quickly followed. Norman’s friendship with The Beatles – forged during his work at Abbey Road – inspired the Fab Four to move in and record “Hey Jude” and most of The White Album. “They could see the potential – they could come along and just try new things and not be in a sterile environment,” Russell said. “Every single musician wanted to work there because it was completely countercultural to everything else that was going on.”

‘I know that voice’

Norman’s friendship with McCartney – and with many of the other artists that recorded at Trident – continued for decades, and some of them were lifelong. Russell recounted a moment when he met Sir Paul in 1979. “I'm standing with my mom and dad and we're chatting and I hear this voice shout, ‘Hey Norman!’” he said. “I go, ‘I know that voice.’

“I look around and there's Paul McCartney walking over to my dad to give him a big hug. And then he turns around and goes, ‘Hey, you must be the kids – which one's Darren, which one's Russell?’ He knew our names!”

McCartney gave Russell a Wings guitar pick before calling over John Bonham to ask him to fetch some drumsticks for Darren. Bonham obliged – this was just a few weeks before the legendary Led Zeppelin drummer’s death. McCartney wrote a forward for Norman Sheffield’s memoir and they stayed friends until Norman passed away in 2014.

An early pioneer of the studio musician concept of keeping ace musicians in-house to support visiting artists who came in with ideas, Norman developed a peerless roster of studio musicians at Trident – luminaries like Phil Collins (Genesis), Herbie Flowers (T. Rex), and Rick Wakeman (Yes) – and could build a first-rate band around anyone.

And Sheffield’s ingenuity didn’t stop there: Trillion Studios supplied music with a film element before most were even thinking about it. And when vinyl shortages created a backlog of studio recordings, he created his own tape studio and pressing plant.

“I was very lucky to grow up in this very entrepreneurial spirit,” Russell acknowledged. And Norman’s son has played a similar tune throughout his own life.

Like his father, Russell grew up playing drums and then moved into the studio as an adult. Surrounded by equipment, he discovered a passion for technology, observing firsthand “how it could transform a sound and transform a business,” he told me. But after spending a lifetime around music, he didn’t necessarily want to apply his technical skills to that industry.

He’d also fostered a love for aviation and had a brief stint in the Royal Air Force. The day before our interview he’d flown a plane back from his mother’s home in Cornwall. The travel industry became a focus of the digital design agency he founded with his brother, and it would eventually bring him into partnership with Eurythmics’ Stewart.

In 1996, Sheffield took a meeting with EasyJet – then just a drab portable office outside of London’s Luton Airport – and ended up winning the business to become the company’s first real digital agency. They proceeded to digitalize EasyJet’s offering, making them one of the first airlines to move to online booking, and in short order, one of Europe’s premier budget airlines.

After his work with EasyJet, The Sunday Times asked Sheffield, who was now a leader in the industry, to speak at a conference on the transformation of travel. As luck would have it, Stewart was at the same conference, discussing Napster’s role in ransacking the music industry.

“We happened to be in the green room and my father was with me. And I went up [to Stewart] and introduced myself. He asked me, ‘What are you here for?’” Sheffield recalled. “So I talked about my work with EasyJet. ‘I love that work!’ Dave responds.”

Dave Stewart

“So this is a guy who knew my work, you know, and I was celebrating the fact I knew his work, and then he turned around to my dad and said, ‘What brings you here?’ And Dad says, ‘I used to run a recording studio called Trident and Dave goes, ‘Oh my God. I always wanted to work at your studio!’” he said.

Sheffield met Stewart again a few days later at The Hospital Club, a now-defunct members club that the Eurythmics artist started in 2004 with Microsoft co-founder, Paul Allen (Radiohead also recorded some of their 2007 tour de force, In Rainbows, in the space).

“I told him about what we were doing with Trackd, and he subsequently invested. He's become a shareholder, a very active advisor in the business, and a good friend I'm pleased to say,” Sheffield said.

Stewart’s also an investor in Songbits, where fans can purchase “bits” of songs and mint them as an NFT. The NFT – which can contain many bits – is collectible, will grant access to special features, and will be tradeable on a secondary market.

Sheffield again drew an analogue between the web3 platform and lessons learned from watching his dad manage Queen.

“At one time, the [Queen] fan club was the biggest in the world,” he said. “People were paying a couple of pounds a year to get signed posters, exclusive first access to gigs, merch… all that built a real community.”

Russell Sheffield with Queen

Songbits seeks to conjure the same energy Queen fostered with their fan club back in the ‘70s – now with the full technicolor power of the blockchain. Fractional song ownership creates an arguably even stronger bond between artist and fan, as additional perks – like access to gigs and merch – are more easily tracked and nurtured, and a secondary market creates additional incentive for fans to participate. To reduce friction, blockchain mechanisms operate in the background and bits can be purchased by credit card.

“The beautiful thing about this medium is that every time that song is played – you hear it in a cab or in a restaurant – you can grin knowing ‘Yeah, that’s mine. I'm in there and I'm alongside my artists. I'm in his gang,” Sheffield said. “And I'm in his gang with 200 or a 1,000 people that also own a piece of that song. I can trade it, and if I don't want it anymore, I can pass it onto somebody else. We’ve taken the analogy about collecting CDs, vinyl, and creativity, stripped out all the technology, and built a platform.”

Tracing the lineage of Songbits back to Trident is a helpful reminder that web3 doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. People building DAOs should remember co-ops have been iterating on collective ownership and governance models for a couple hundred years. Builders trying to shoehorn utility into NFTs should examine how Queen’s – and many others’ – fan clubs were successful long before the internet existed, let alone the blockchain. At the end of the day, tech is a means to an end, not the end itself. If music stays at the heart of the matter – if musicians build for each other, and stay true to that identity through thick and thin – perhaps web3 will get its own Trident Studios sooner than we think.